O God, the Eternal Father, we ask thee in the name of thy Son, Jesus Christ, to bless and sanctify this bread to the souls of all those who partake of it, that they may eat in remembrance of the body of thy Son, and witness unto thee, O God, the Eternal Father, that they are willing to take upon them the name of thy Son, and always remember him and keep his commandments which he has given them; that they may always have his Spirit to be with them. Amen.

Every week I would kneel in the front corner of the chapel, behind the table on which the sacrament rested. Behind the bread I had just broken into bites, and the scores of tiny plastic cups shimmering with water, I would push back the white lace tablecloth to open a little drawer that revealed a microphone. Then, on behalf of the entire congregation, I would recite the prayer. With all the gravitas I could muster, I asked God to turn bread into an instrument of forgiveness. I spoke slowly and clearly, trying to inflect maximum importance into each word and phrase. Every week, the same prayer, word for word. When I was done, I would stand up and look to the leadership on the podium. A nod from the ranking leader confirmed that the prayer was spoken correctly, and the bread could be distributed. A shaking head meant the prayer must be repeated until correct, verbatim from scripture.

The Mormon tradition is for the sacrament to be administered by teenage boys. Sixteen-year-olds bless the bread and water, and the younger boys carry the trays up and down the pews. Since my congregation had few teenagers, I prayed every week. And nearly every week I received compliments on my prayers. “I can really feel the spirit when you pray.” “Thanks for praying with such reverence.” “I can hear the faith behind your words.” I’m sure some of it was just people being friendly. But there was one person whose opinion I especially valued: a retired opera singer and voice professor. He often told me, “I love hearing you pray. You have such a rich voice. You’ll go far with a voice like that.”

Without paid clergy, Mormons rely on regular members to give the sermons. Most adults can expect to give a 15-minute talk about an assigned topic once every 2-3 years. In my congregation, most teens were asked to give a 5-minute talk about once every 9-12 months. At 12, I was confident. A talk was a short anecdote, a couple low quality church jokes, and a nice moral at the end. It was exactly what I had been groomed to do my entire childhood. Preparation was annoying, and there were high expectations derived from having eloquent parents, but delivery was easy. I had a voice, and a little swagger to boot.

At 16, it was different. A little more substance was expected. While my skill as a writer had improved, my belief in what I was saying had collapsed. By that point, the only idea of God I found tenable was a non-interventionist God, not the kind you brag about over the pulpit. I was good at playing a faithful kid in Sunday School, and reciting the scripted prayer over the sacrament. These were other people’s words, other people’s ideas, and I was just a messenger.

These acts were part of keeping the peace with my family and church community. I could justify this deceit to myself. Crafting my own words together and delivering them in public felt much more personal. I could not separate myself from the words I spoke over the pulpit in the same way I could separate myself from the words I spoke blessing the sacrament. Lack of honesty in this context led to much more self-loathing.

Writing a talk became a torturous exercise in finding middle ground between thoughts I was willing to present as mine and things that could be said over the pulpit without people trying to stage an intervention on my behalf. I was never proud of any talk I gave in high school. The gap between what I wanted to say and what I was willing to say led to watered-down content, and the dissonance led to uninspiring delivery. Confidence can be powerful, or truth can be powerful, and I offered neither.

I first came home from college for a weekend in October of my freshman year. Over the summer, I had finished my Eagle Scout project, and I needed to complete a final interview called a board of review to receive the award. My interview panel consisted of two men from the local Scouting Council I’d never met, affiliated with a different local church, and one man from my church. They asked me a lot of questions about values: What had I learned from Scouting, and how would I apply it to the rest of my life?

I told them that in my first months of college I had witnessed the importance of having clear values. I played up the Mormon trope of secular universities being institutions of sinning. I said I had seen people with no discipline, neglecting responsibility, eating and drinking their way into trouble, in a state of constant indulgence. My moral education taught me about the weight of my actions, allowing me to focus on more important endeavors. This was partially true. I’d seen many peers struggle to adjust to life without adult supervision. The panel nodded and agreed. These were the things they wanted to hear.

The whole truth was more complicated. For the past four years, I had felt increasingly uncomfortable with my religious upbringing. I wasn’t sure what my values were, just that I wanted to reevaluate the ones that Mormonism had instilled. I decided that my priority was academics, and that everything else would need to fit in around that. But I had second thoughts about this too. My first two months of college had been rough. I worked too much and slept too little. My overwhelmed immune system could not keep up, and that weekend I was very sick, feverish, and sleeping for 15 hours a day. Illness aside, I wasn’t enjoying the college experience. My more indulgent peers had more fun.

At the start of the board of review, I was asked to recite the Scout Oath and Law, promising to do my best to “keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” As I evaluated my life at that moment, I felt I was none of the three. But I said the right things, passed the board of review, and became an Eagle Scout. I didn’t mention it in the interview, but it was a Sunday, my third consecutive week of deciding to skip church. I haven’t been back since.

I had the Eagle Scout Ceremony a couple months later when I was home for Christmas. Many of my friends from Church were there. It’s a bit like attending your own funeral. My mother did a bio of my childhood, skipping all the unpleasant parts. A couple of my Scout leaders thanked me for being a role model for younger boys. I got up and told a few stories from my time in Scouting, thanked my leaders and parents for their support, and offered encouragement to the younger kids. While I meant everything I said, I felt like a fraud. I wasn’t the person being described.

An Eagle Scout award must be finished before the Scout turns 18. I had done about 90% of the work by 14, rarely attended for three and a half years, and then finished in a hurry at 17 the summer after I graduated high school. I said I was busy with schoolwork and extracurricular activities, which was true, but not the reason I couldn’t find any time for Scouts. When I first became religiously disillusioned, I wanted to stop going to church. My parents refused to let me neglect my primary religious obligations, so as an outlet I neglected my secondary Scouting obligations. I didn’t bring this up at the ceremony.

All the Mormon programs for young men focus on preparing boys for full time missionary service. Boys can choose between beginning a two-year mission at 18 or 19. Since I was young for my grade, graduating at 17, I’d spent years deflecting queries about my plans for a mission by saying I would go to college first. At no point did I ever intend on serving a mission. By the Eagle ceremony, I was a few months past 18. I should have been submitting the application and preparing spiritually and mentally for a mission. I wasn’t. I hadn’t even been to church for three months. I didn’t bring this up at the ceremony either. The person who was presented the Eagle Scout award was held up as a role model. I didn’t think the younger boys’ parents would want their sons emulating the real person.

The last person to speak was the Bishop, as lay leaders of Mormon congregations are known. He had just moved into town and had been appointed to the role after I had gone off to college. I wouldn’t have asked him to speak, but as the highest-ranking religious figure attending, some brief remarks were the norm. He acknowledged that he had barely met me, but from the prestige of the Eagle Scout award, the words at the ceremony, and knowing my family, he was sure that I was a first-rate person: someone he could trust, someone he would want to hire, and someone who would go far in life.

Why not be more open about my doctrinal concerns, my lack of faith, and my plan to not go on a mission? As anyone who has had the missionaries show up on their porch knows, Mormons don’t do well with boundaries. It’s a high-demand religion, and anyone who doesn’t fit the mold is singled out for extra attention. As a teenager, expressing doubts will cause youth leaders and fellow members to conclude that you need to do more faith-building activities. I would be subjected to more frequent assignments to give talks or teach Sunday school lessons, more nagging about scripture study, more invitations to go teaching with the missionaries, and more scrutiny of my behavior. Consistently declining invitations for more responsibility would raise additional concern among leaders, feeding a dangerous cycle.

What I wanted was to be less involved, or not involved at all. Constrained within parental requirements to maintain a basic level of involvement and the appearance of interest, the best I could do was to minimize the unpleasantness.

With a structure requiring so much member participation, performance art is baked in to Mormonism. From the time they can speak, Mormon children are encouraged to publicly express their faith. As is true outside of Mormonism, strength of conviction cannot be directly measured, so strength of presentation is used as a proxy. As a child, I knew who to emulate. I wanted to be like the leaders who spoke with confidence and certainty. I learned to deliver with poise and gusto. The words and ideas mostly belonged to others, but the confidence was mine. As I matured, I lost confidence in the meaning of the words, but not the art of delivery.

The sacrament ceremony takes about ten minutes. There is a song, the prayers over the bread and water, and quiet in the chapel while the sacrament is passed out. It’s supposed to be a time of reflection, for seeking forgiveness for sins.

I often reflected on the absurdity of my situation. If I was administering this ordinance, and I thought it was futile, did that make it so? According to Mormon teachings, my lack of faith made me ineligible to exercise the priesthood power required to bless the sacrament. Every Sunday, priesthood leaders verified that I spoke the words correctly, verbatim, but never verified that I believed what I was saying.

It’s crazy that I was allowed to keep doing it. Surely someone would notice and make me stop. Week after week, no one ever did. When it came time to pray, I would clear my head, kneel, and speak as I had been taught.

O God, the Eternal Father, we ask thee in the name of thy Son, Jesus Christ, to bless and sanctify this bread…

People loved it. They could feel the conviction, they said. I had such a nice voice, they said. This made me feel both powerful and ashamed. Even the vocal professor, who must have known delivery was a skill, could be fooled. Part of me liked the praise, but it was wrong. I had words, written by someone else, and practiced vocal chords. But I had no voice.

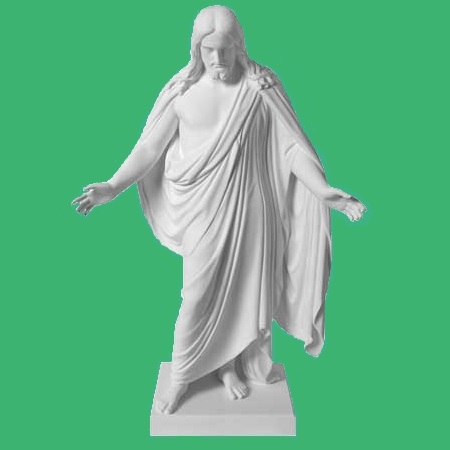

Part of my reluctance to be authentic stemmed from my own discomfort with my new ideas. I missed feeling like a child of God, created in his image, a being of divine origin, growing and learning toward perfect knowledge and eternal glory. The world seems darker as an undersized primate, separated from the worst human impulses by tenuous social norms. I wish I could return to the brighter view of humanity, but I find it indefensible. When knowledge feels like a burden, is it ethical to allow and promote ignorance? It’s as though I adjusted the aperture on my worldview, learning through the process that all my old photos were overexposed. The darkness allows for more color and depth. I am better able to make informed decisions in the world as it is. But to those in an overexposed world, the darkness feels threatening, and the messenger ominous.

On top of my personal discomfort, I was afraid of the social cost of expressing doubts. Mormonism handles dissent less by addressing concerns than by increasing the cost of dissenting. Church positions are correct, and not up to interpretation. Dissent is disloyal, and thus reflects poorly on the dissenter. In a culture with so much social capital derived from public displays of faith, spiritual concerns are undesirable – if not threatening.

As a teenager, I felt a crisis of authenticity, which grew with the gap between regressive Church policy and 21st century life. Living at home made leaving Mormonism impossible. With the cost of public doubt also high, I felt forced into feigning faith. I often had to pick between following my conscience or following the Prophet, and for a long time the Prophet won.

In my experience, the emotional toll of being inauthentic increases over time. For me, the inflection point has been reached. I’m not going to settle for being an orator. I want a voice.

"Demons," Imagine Dragons